Citiți acest interviu în limba română aici.

There are people whom, although you see them for the first time, you have the feeling that you are seeing them again, that they have been part of your inner world for a long time, only that you have never had the opportunity to sit next to them and have a meaningful talk with them. That's why when you're finally face-to-face, the boundaries of the real world are suspended, and the words flow naturally and gather into stories that you wish were endless. Meeting with an artist you have only just discovered, but whom you already admire, is experienced even more intensely. I had the enormous joy of such a meeting, during the Astra Film Fest in Sibiu, with the American actress Melissa Lorraine, protagonist of the documentary Performing Juliet (dir. András Visky, 2021). Made on the principle of storytelling with drawers, the film follows the way life and theater intertwine in Melissa's existence, recreating the period when she performed the role of Juliet in the play of the same name, written by de András Visky in 2002. I saw the documentary before the festival and I was impressed by the authenticity and talent of Melissa, who brings her suffering from life to the role on stage, hoping that the role, performed with all her being, will help her find, like the character played, that kind of love in front of which death has no power. The magnetic look, the force put into play, the emphasis on the strong emotion conveyed through simple but effective techniques, the courage to confess her fears, her rebellious spirit, the extraordinary sensitivity are just some of Melissa's features that made me want to be able to see her play at the Astra Film Fest. I didn't even dare to dream that I would have the chance of interviewing her, but I'm a lucky person and my unspoken thought reached Răzvan Penescu, and he helped me turn it into reality. The same man who, in 2003, believing from the beginning in the strength and artistic value of the text written by Visky, published on LiterNet, the Romanian translation of the play, bringing before the readers the real story of a mother with seven children, who is deported by communists in Bărăgan, at the end of the 50s, the youngest of the children being András Visky himself. (the book - in Romanian - can be downloaded for free here).

I spoke with Melissa the day before she played the role of Juliet again, a defining role for her career, on the Thalia stage in Sibiu, as part of Astra Film, a show scheduled before the screening of the documentary Performing Juliet. I wanted to interview her, but the interview turned into a discussion that took its own course, opening doors to Melissa's world, rich in intense experiences transformed into performance-rituals, which help her discover truths about her and about the world. We talked about her inner world, about what she understands by theater, about the way she relates to the public and her connection with theater in Romania. I left the discussion open, because I just couldn't bear to ask her one last question. We promised to meet again for a real interview and continue to talk about her very special way of existing in the artistic and real world alike.

Ioana Clara Enescu: I would like to start our interview with a sentence of a famous contemporary American microbiologist, Bruce Birren, who, in his article, Of Microbes and Men (Boston Globe, 2008), concludes that we are not individuals, we are colonies. Continuing his thought, Andreas Weber, a marine biologist, says that we should not refer to ourselves using the pronoun I, but us, because inside us live millions of other creatures, and they shape our world. I think that our souls could be the same, entities that contain, and are shaped by a multitude of other elements. So, I'd like to start from here, asking you what does your soul contain, Melissa? What are the colonies that inhabit you? Maybe people, maybe places, maybe experiences.

Melissa Lorraine: Yah, ok, so I was born in France, one of the facts about me is that I never know how to answer where I'm from, because I was born in France, but I'm not French, and my father was born in Nigeria, but he's not Nigerian. And ethnically I'm Armenian, but none of us have ever been there, I mean since we escaped, so I was raised in France until I was 9 and moved to Chicago when I was 9, and was very much shaped by America, but even shaped by America when I was in France, because, at the time, America was kind of the Mecca, you know. Even before I arrived in America I was dreaming of America, so then I arrived there and then it's a slow process of disillusionment, because America is not what anyone thinks it is, so I think there is an ethnic confusion, a sense of global citizenship that is a part of the confusion inside of my heart of where to be, and, interestingly enough, somehow, when I discovered this play (Juliet), I found that my heart lived here, in Romania, which I have nothing to do with, you know, so I think I have a feeling of finding my home in people, more than anything, I have a ling list of experiences like András, where I have known you always, but I've just met you, you know, so I follow this thread in the world of people who are clearly my kin, but I just discover them.

I.C.E.: Maybe they live inside you, and you just discover them.

M.L.: Yes, it's a felling of myself, look, it's me. And then, the other schizophrenia I think that I have struggled with is a religious one, of course, because my parents were missionaries, and my grandparents were missionaries so this long lineage of Christianity that I resisted very aggressively as a child. I'm the youngest of four, and my parents intended to have only 3 children, and so I had this feeling of being accidental, and so I fell accidentally in the family, too. All of my sisters very much got in line, behind my parents, no problem, but everything they were trying to feed me I could not swallow; it was just a guttural refusal of what I was being taught. So then I went into a long period of rebellion, which was somehow reconciled also by this play, because inside this play there was everything. All of what I most appreciated about it was that András's idea of spirituality was so concrete, so true, that it could be desecrated, it wasn't so fragile that you had to be polite. You could really have a fist fight with God if you wanted to, and he would love it. And this was like ah! Because I've always wanted to have a fist fight with him, but I've always been told that this is not proper, so something in the play made space for my testimony of the world where I know what I'm supposed to think, but have you seen what is happening, I don't understand the relationship between what I am supposed to think and the truth, or the reality. And his play made space for me to have a / to not be crazy, that my experience of the world was legitimate, and my anger was founded, and God is, in fact, very unprofessional, you know, because this is something that Andras always talk about - we have a very unprofessional God, and Andras invited this possibility that we could manipulate the situation, that is not just a one side, it's a dialogue, and God / whatever is asking that we participate in the manifestation of reality, and he will somehow respond when we demand something, but more than that that he is really hoping that we will demand something more from him, from the reality. And this felt like, Ah, finally, I have a place in the story, I'm not just a victim of circumstances, who has to nod, and bow, and obey. So he really helped to put back together the multitudes of myself, because also I think I ended up in the theatre as an act of rebellion. The theatre is not a place for a good Christian, and Andras had really taken possession of the theatre as something that can be made holly.

I.C.E.: My second question you've already answered - what was the thing that draw you to the play - of course I had a lot of possible answers in my mind, and I think you checked them all. It's a play that helps you discover yourself, even if you have nothing to do with that kind of experience.

M.L.: Exactly, because part of the problem was that I wanted so much to wash the religion off my body , it was put on me, and I didn't like it, and I didn't want it, and it didn't make me feel good. And I kept trying to get rid of it, and I was also embarrassed to have this kind of obsession, because is not fashionable in my generation to have any relationship with the spirituality, so it was like an embarrassment, I was almost like obsessed. Even if I was saying no to it, it was still something I was dealing with. I couldn't change the subject, and this was embarrassing. So the play also somehow forgave me for the obsession, like it validated that this isn't a really essential issue, it's not a peripheral, it really allowed me to confess that it is really at the center of my own humanity and it gave me the words to confess why it's at the center of my humanity and what's so nice about the way he writes it is that he doesn't allow the audience to step out of the issue, personally, to say that, Oh, OK, this is yours. It's not possible. We are here, this is the situation, feel how you do about it, and that was also so refreshing in contrast to missionary philosophy which is them trying to change you. Nobody is trying to change anybody, we are just trying to really wrestle with the given circumstances together, because we need every witness in order to discern what's true and know how to find our way forward so his approach to the subject was very refreshing compared to what I had ever discovered in the West on the subject. The idea of a Christian play is almost disgusting to me, you know, it's like, please, please, let's not ever do that. So again, the way that Andras's perspective on what it means to be in a relationship with the divine or whatever it was so creative, like I decide what it means to converse with you.

I.C.E.: And still, it's not heretic.

M.L.: It's love. And you know that if you really show your ugliest side they will forgive you, it's ok.

I.C.E.: I read that you played more than 300 times Juliet, in a lot of places, from Palestine, to prisons, and in international festivals. I saw a picture of you on internet, and it struck me to see you surrounded by Palestinian soldiers. This is not a very common image of an actress touring with here play. I was wondering - are there any stories worth to be told from your tour?

M.L.: So many! I'll chose two. One was in Palestine, one of the craziest experiences of my life. I performed in Jericho, and it was for a room full of Palestinian farmers who had never seen a play, and who didn't speak any English. And the play had no subtitles. And I'm in a room with two very small lights, and one moment, one of them dies, so there is just one tiny light on me, so there is berry any light, I'm speaking the text and the entire room, all the people inside are speaking to each other at full volume, trying to tell each other what they think I'm saying, through the whole show. And for me it was one of the most difficult performances of my life, you can imagine, because I can't focus, I mean it feels like I'm in a bar performing, so I leave the stage and I feel like that was just nothing, what was that even for, and a little child walks passed me outside the theatre and gives me thumbs up, and I look at them like, well, that's nice, but I look at them as though I didn't receive the compliment, so they keep getting the gesture until I finally say thank you, and then I hear them in the next room trying to interpret what's just happened, and I just keep hearing Allah, Allah, and I just though I don't know what I'm doing, but I'm doing it, you know, like I felt so small inside of this very strange circumstance where I still today don't know what I did.

I.C.E.: But why / how come you ended up there, with people not understanding English, with no subtitles. What was wrong?

M.L.: It's not wrong, it's always like this. My whole tour of this shows it's just been an act of obedience. Even this performance, I didn't have a production of Juliet ready to give this festival, so we have invented one for this festival, this week, yesterday, today, tomorrow, we are inventing one. And someone said to me in Chicago Well, you could say No, and someone else heard them say that to me, and they said What are you talking about? It's like a phone call from her mother, you know? So, I can't say no to this show, even if it's totally impractical. So, somebody wanted that I do it in Palestine, and the answer was yes, and then I figured out how. And of course, I questioned whether it was worth it, but I have to trust, you know, so this was maybe the hardest performance. I mean when I kept hearing Allah, Allah, I don't know how to explain this, even the fact that they were able to take the story and make it theirs was so moving to me had such a wonderful feeling of it's not my problem, I just come and I say the text and I hope that it means something, somewhere.

My second story is in the prison, I went to a woman's prison to perform the show and all the prisoners are being brought out into the chairs, to sit, and I am sitting at the back, and I can feel the room is cold, the prisoners are not interested in whatever this is that is about to happen, and so I am very nervous, it was the firs time I had ever been in prison and I felt so small and scared and we were waiting the government officials to arrive, so we were all sitting in silence waiting for the government officials to arrive and then they got in front of me and announce that I was here to perform pro bono, and for whatever reason, that fact changed the temperature in the room. As soon as everyone realized she's not here because someone paid her to lecture us, she is here because she wants to give us something for no money, so everything in the room changed and I got up and I started to perform the show and in one moment I turn away from the audience for a moment of privacy, just to gather my thoughts, and I realise there are prisoners who are not allowed to come out of their cell, they were in trouble for some reason, so they were left in their cell, and they are standing at the door of their cell, and they have a slid right here for their food, and they are standing with their ear like this, for 90 minutes and I didn't realise until I turn around in the middle of the show when I see this other choir of angel stuck in this crazy position trying to feed of whatever it is that I'm doing and I just felt like there is better be worth this pain, so I finished the performance and the prisoners, the women, are on two different levels, and they start to applaud, and it was like a chaos, like a riot, of applause, the craziest, some people stood on their chairs, crazy response from this audience, which the normal world had never given me, but I was giving them their story, you know. And so we had a conversation afterwards, and they were asking me something about this play, and I said, when I first met this play I thought, ah, now this is the kind of relationship I want to have with God, and so I thought I could adopt her belligerence - it feels much better to be belligerent to God, and then it hit me that this was a misunderstanding, because he has a love afgfair that is so much deeper than mine, that she has arrived to a place where she can be belligerent, but maybe I'd take my time to get to that point, and I said something like the fear of God is important, and the whole room said Mhm, like a choir. It was the most interesting negotiation of how to deal with God. And then I told them afterwards, if you get out, please find me, I would love to meet you on the outside.

I.C.E.: And has anyone ever contacted you?

M.L.: No, not yet. But I remember afterwards I went to get a drink with the warden of the prison who had invited me to come and perform, and I said to him I was a little nervous of performing this show in a prison, because, of course, Juliet is in prison unjustly, and I don't want to suggest to these women that it's unjust that they are there and they should be so bitter, and his response was, Melissa, are you kidding me? All of these women are incarcerated unjustly, if they were white, or they had money, they wouldn't be here, and this was the warden, who had the awareness that this institution which he runs is a complete shit, and was able to open my mind, because I had the idea that Juliet was this kind of woman, and they were that kind, and he made them the same. And it was the beginning of understanding our prison system and then it begin my kind of addiction to serving these kind of spaces.

I.C.E.: I saw that you use your own experience, your own suffering, and you bring it into the theatre and then you show it to people and they can find their own suffering there, and you do it with Juliet, with The Camino Project. You have this way of feeling that theater is more than art, is more than aesthetics, it's catharsis, as it used to be in ancient times, how do you find this enormous amount of energy that you use to do these kinds of performances, what feeds you with energy, to be able to give so much to your audience?

M.L.: For me, why I practice theater as a ritual is because I have found that the theatre cannot lie, in the way that the church can lie. Meaning that in the church, when I'm listening to the words, I am constantly wrestling, negotiating, am I being manipulated, is this true, how do I feel about this today, am I stupid, am I swallowing something because it feels good. Theater, somehow, because it's empty, because it's no dogma, because it's just an altar where you can burn things and see what remains, I feel more trust I feel like what I see manifest in the theater I can believe, because nobody put it there, it happened, it manifested, so it must be, so it's become a kind of church for me where I can test every day so that I am sure.. I am very afraid of becoming delusion, and getting lost, and going down a path and not knowing how to come back, because I've gone so far, so for meit's like the ritual of theatre is starting from zero again. I don't want to believe everything that I believed yesterday, I only want to believe what's true again, because if it's not true anymore, then who cares, so try it, agai, try it again, try it again, and so it's this kind of experiment that is something I need in order to know how to be today, and without that I know I will be confused, and in part is because I'm an actress, so I can believe anything, you know, and I have a professional imagination and it's very dangerous, so I have to keep putting the things that I think might be true into the fire again, and I feel inside of this ritual a huge source. It's not a place where I spend myself, it's a place where I refill. After a performance I don't feel tired at all, I really don't, I feel more, larger, so I've had a couple of moments, it's very rare, but I've had a couple of moments in the thater where I really discovered a truth, not even tested, but discover it, it came out. I can tell you one moment. It was another Visky play, called I killed my mother, which was the second play he wrote for me, and it's about an orphan, and she has a best friend, the best friend dies saving her life, and she continues to live and her life is really, really hard, and in one moment she is very angry about the situation, I won't gop into what happened, but it's really a betrayel from the universe, and she is supposed to rage at the audience, like throwing imaginary stones at the audience, and were rehersing the scene, and the friend who was dead is still on stange with me, but he's dead, you know, we are not in the same plain, and the director came to him and whispered something in his ear, and didn't tell me what was going to happen, and said, ok, go back, and redo the scene when you come and throw imaginary stones at the audience, and so I started to do the scene , and to throw the stones, and in the corner of my wye I see him running towards me and my body reacts like with fear, because I don't know why he is running at me, and then suddenly I realize, no, he is not running at me, he is beside me and he is throwing stones at the audience, and everything in me just broke, and I couldn't even explain what I was experiencing, but what I was experiencing was that I needed to feel that in a moment like this I am not the only one who is angry, that is it angering, but it would have been one thing in that moment it felt like oh, wouldn't it be nice if you had a friend, who is also throwing stones, what I felt was this is true, I have a friend who is also throwing stones, and it was the second thing that was the kind o breaking poit, the realizations that it's true, it's not just something you need, but I can't explain how that happens inside of these games, but it does. Sometimes, a game is not a game and you can feel it with every cell of the body, that's not a game, that's real, and in no other moment of my life would I see it so clearly as this moment, because every other moment of life we are just of hoping that maybe someone is on your side,they are feeling as angry as you are on their circumstances, so, anyway, it's those kind of miracles that occur every so often, that keep you close to the fire, that you are waiting, you are listening, you are hoping for another truth to be exposed in a way that you can really believe and keep it. But then, again, not keep it, try it again tomorrow, to make sure it's true.

I.C.E.: What about your relationship with you audience? I read in an interview that in Chicago, in Theater Y, after every performance you talk to the audience. You expose yourselves, it the whole theaters' idea to show what happened, what you felt. In this exchange with the audience, what do you receive? Are there moments in which they help you understand better or change anything that you thought?

M.L.: Yeah, definitely. Honestly, part of why we have these conversation is because of an American tragedy, which is that Americans are very insecure in their interpretive skills. This dramaturgy from Eastern Europe, what Andras writes, what he calls kind of a mosaic dramaturgy, where he gives you just this little glimpse, and then this one there, and then you zoom out and aaa, and this is because he feels very strongly that if you understand everything, you understand nothing. If he deprives your mind of logic, you use all your other parts to try to make meaning and you have put yourself into the gaps, to connect them, but this is very unsual for America, so we find that audiences in America want to make sure that they got it right. They need to check - what did you mean by this / and we are very happy to offer that space, you know. Anyway, so it's just a very interesting difference - I think if you performed here, the audience might not want to have this conversation, because they feel very confident with what they receive, and they don't need anybody's help. So just to say that this is kind of what I feel is an American necessity, because we are giving them a different meal than they are used to, then we have to be open to helping them process it, understand it, and in some ways even educate them on how to come in the next time, with more confidence in themselves - you can do this, you don't need us to... but, more than that, I also really like that space to talk, because, otherwise it feels too transactional - you paid the ticket, I give you this thing, thank you very much, I will go rest, you go home, but, for me, the reason for theater now is because I feel that my culture used to have the opportunity to convene, to assemble, in the church. That was the space where we all come together, with every level of society, together, to work through our problems. Of course, the church is dying, so then what is that space, when do we all gather, and so when you have a real gathering of all the people, and you don't allow them to meet each other, this is a missed opportunity. So, my philosophy is always: this is a one-time experience. This group of people will never be together again, why would we waste it, say it's enough, let's go home? Stay, let's be together, let's see what more we can discover from this event. So, I'm fully addicted to the conversations somehow, and it's important to me that... the other thing that happens in America with these conversations is that the production will come out and ask the audience questions like kindergarten class, like what did you receive, did you get this, oh, how do you feel about this, no, this second half of the evening is your time, I had the whole first half to do what I to do, to say what I had to say, and so, when we start the conversation the people often expect us to lead with some kind of prompt, and I refuse, so often it starts with a long silence, and I tell my company all the time enjoy it, lean in, this is fine, we are not filling the silence, we are waiting for something that they need, and they can ask anything they want, I'll answer the best of my ability, and we try to go as long as there is interest to go on, so it's really their time, so for me it balances this event. I had my time, now you have your time, this is not a one-way street. So trying to just invert the expectation of the theater, and the other thing, which I'm sure you know about András and his theatre is the Barrak Dramaturgy, so the issue is that we can't leave, until we've arrived somewhere new, and that might take a long time, and we have to stay true to that intention, we can't be easily satisfied with the evening, if we haven't got this, if we haven't arrived somewhere new, then we have to stay longer. So, he invented this kind of, no, the door is still locked. Even the politics of the show is sometimes complicated, so sometimes you go into tense questions.

I.C.E.: I'd like to come back again a little to the context that brought you here, because I'd like to ask you what are your links with the Romanian theatre? What draws you back again and again here? Are there only projects you work with András Visky or is there something more?

M.L.: I have to tell you honestly, that when I first came to Cluj and saw the productions at András's theater, I really wanted to join Andras's theater. Really, with all my heart. Like this was where I... I can't even describe my experiences in the theatre - for example, I had one experience of a production of Uncle Vania, at the Theatre in Cluj (directed by Andrei Șerban), where I didn't cry at all during the how, but when it came time to applaud, I just cried through the whole applause. I don't know how to explain that, it had never happened to me in any other theatre, so these kind of.... I mean, ok, in America, or in many theaters, the theater satisfies itself with entertaining, and when I arrived in Cluj, I felt very strongly that the expectation was much bigger. And I could even feal... I feal in Romania that Romanians have the experience of losing the right to assemble, and so the theatre is holly, and when the people enter the theatre in Romania, they enter like they are entering a church, and this is not the way it is in America. So, I mean, it was a whole new level of reverence for the form that I felt, both from the public, and the actors, just a higher expectation. So, I wanted to join this theatre company, and Andras said no, Melissa, I hate to tell you, but you really must play in your mother tongue. I had the experience of playing in Hungarian, I knew that he was right, but it was heart-breaking for me to realize I could not just join this work. I hat to try to make this work where I am from, which is why the theater company, you know, but I think I struggle because I can't import the reverence, I can't get the American audience the reverence for the form, that Romania has earned by loss, there is no short cut to that kind of reverence, so I come here to remember how it can be, how it might be, and then I go back, and then I say...

I.C.E.: And then you go back, and create such impressive experience as Juliet, or The Camino Project... I am sure people come to Chicago to your theater just to be a part of this kind of experience. You must get some feedback from people who see your shows, your company shows, and they say this is something I've never seen, I'd like to come back. I am sure you get this kind of feedback.

M.L.: We do, and it's true, that people can feel that there is a difference.

I.C.E.: And this is because you put depth, you put yourself in your shows, completely, truly. And even if the audience might not understand everything, as you've said, they feel it, and it can be enough.

M.L.: Or you don't. some people say what is this. So that may be the biggest challenge, to stay true to the objective, whether is misunderstood, or not. I know what I am after, and I have to allow some people to spit it out. Because, ok, of course, it's not for you, and there are the ones who say I could eat this all day.

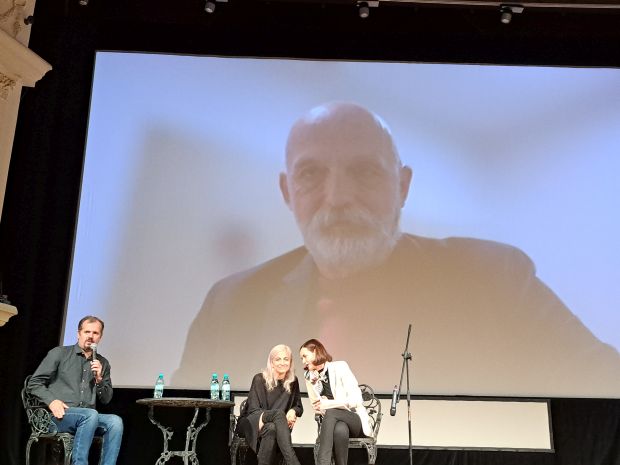

Post Scriptum: The next day, I admired Melissa playing Juliet on the Thalia small stage, in the show created especially for the festival, in a few days, which was not the easiest experience, because she had to quickly learn the new version of the text, shorter than the original one, and it was the first time that, next to her, on stage, there was another artist, the violinist Albert Márkos. During the performance, the cello turned into a bell, into the wind, into the worried voice of the mother or into the serene laughter of the children, supporting the actress's play and punctuating the moments of maximum intensity of her monologue. Melissa's voice with countless inflections, her electrifying gaze and the depth of her playing built a believable Juliet, a feminine presence that impresses through the mixture of strength, grace, suffering and hope, through the meaning given to her life by a love that nothing can bring to its knees. My mother put history in quotation marks, said András Visky, at the question session moderated by writer Radu Vancu after the documentary, explaining Juliet's choice in the play not to divorce her husband in prison, thus bringing the character back to reality. Interpreting the role of Juliet, the actress Melissa Lorraine put the artifice of dramatic art in quotation marks, playing on stage, with extraordinary authenticity, the life of a woman to whom she lent a part of herself.

In theater I can test the truth every day - Performing Juliet at Astra Film Festival, 2022

Ioana Clara Enescu, an interview with Melissa Lorraine

0 comentarii

Arhiva rubricii

Nici măcar nu îi mai conduci, ci le dictezi propria declarație a acelui moment!, Marius Constantinescu, un interviu cu Vadim RepinÎncerc să mențin mereu vie comunicarea, Marius Constantinescu, un interviu cu Hilary HahnCoabitarea în realitatea tehnologică - Speranța nu urcă niciodată cu liftul, Răzvan Rocaș, un interviu cu Toni NicaCa interpret de operă ai provocarea uriașă de a încerca să supraviețuiești în fiecare zi, Marius Constantinescu, un interviu cu Max Emanuel CencicHeartefact. Politică. Teatru. Fabulamundi. Playwriting Europe. New Voices., Anda Cadariu, un interviu cu Patrik LazićToate articolele din această rubricăRubricile categoriei

InterviuriLa persoana Ificti.on.allBibliopolisO săptămînă de prieteniAutismul, din interiorPrimul an de publicitateÎnsemnări mediavitaleJurnal de actor / actriţă în izolarePublicitate